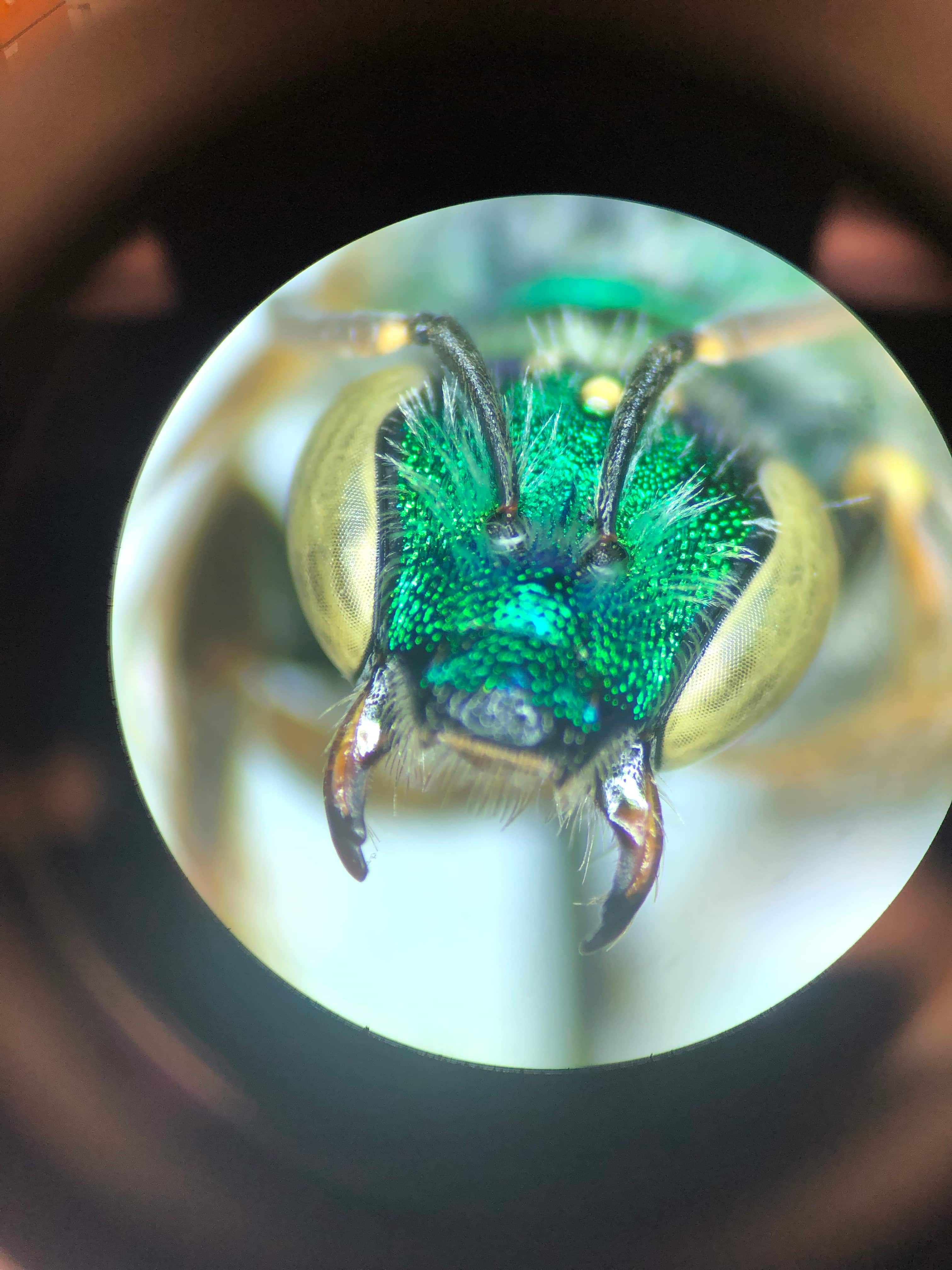

DENTON (UNT), Texas — Most Texans picture honey bees or bumble bees when they think of pollinators, but the majority of the state’s native bees are solitary insects that make their homes underground — and new research from the University of North Texas shows those underground homes depend heavily on soil conditions.

“In Texas, we have at least 1,300 native species, and most of them nest underground,” said Elinor Lichtenberg, assistant professor of biological sciences in UNT’s College of Science. “They’re solitary species that mostly dig out these nests in the soil.”

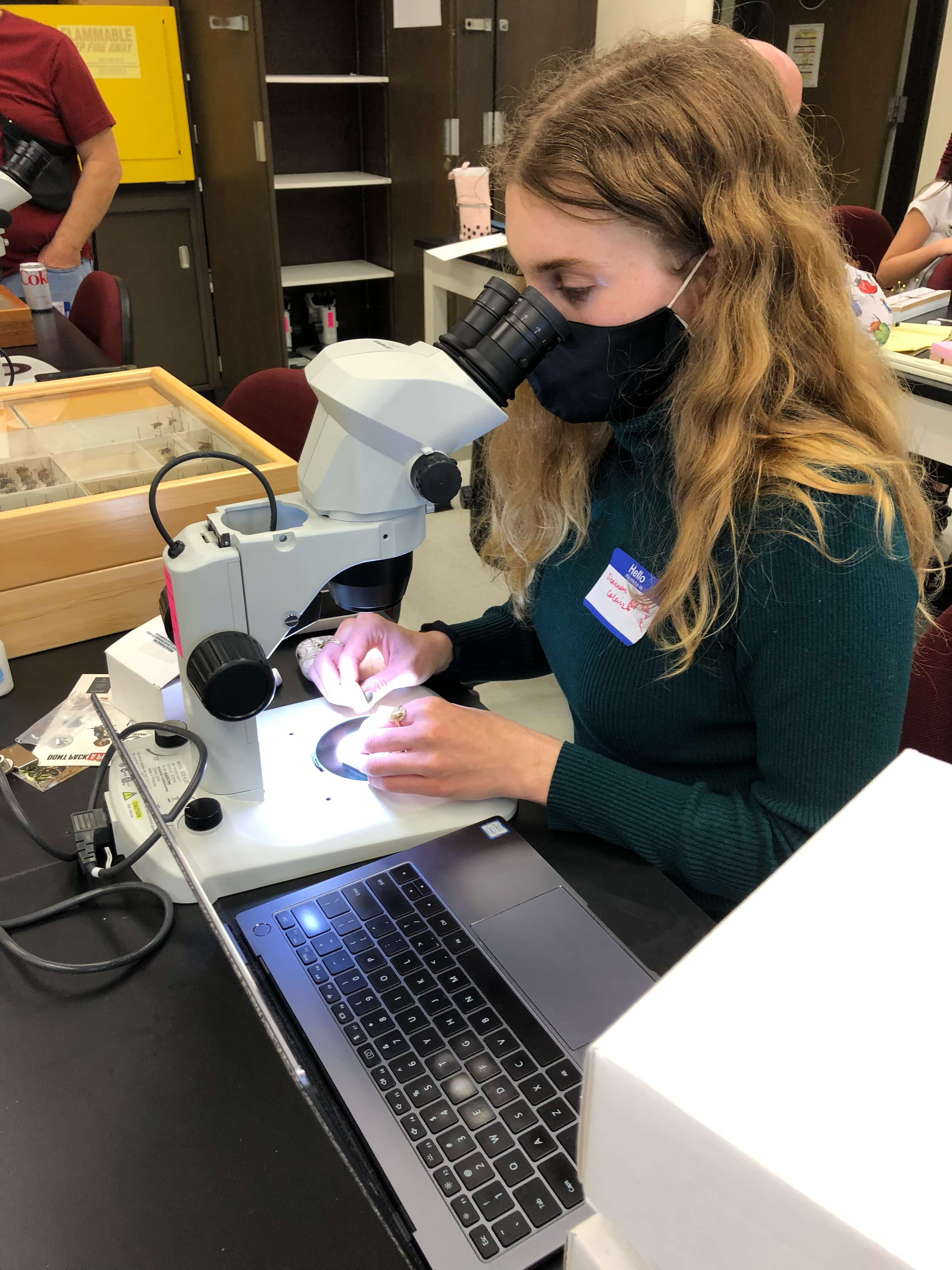

Lichtenberg and Shannon Collins (’23 M.S.) led a study to better understand the habitat needs of these ground-nesting bees. The project, which took place on ranches owned by the Dixon Water Foundation, combined Collins’ interests in soil science and pollinators.

“There’s been relatively little research on ground-nesting bee soil habitat, so I thought ‘why not bridge that gap,’” Collins said.

Over two years, the team collected bees and soil samples across the seasons. They used tools like bee bowls — traps designed to mimic flowers — and hand nets to capture bees, while soil cores helped them extract and study the underground environment.

“To measure soil texture, Shannon worked with Reid Ferring from the geography and environment department,” Lichtenberg said. “For identifying bee species, we received support from Karen Wright, who was the curator at the Texas A&M Insect Collection at the time. We’re really thankful for our partners on this project.”

Their findings, recently published in the Journal of Applied Ecology, revealed that soil texture — not surface factors like floral variety — was the most influential factor in determining where native bees chose to nest.

“We have a lot of clay soil in North Texas, and we found that the proportion of sand made a big difference,” Collins said. “Bees seem to prefer a balance — enough clay for structure, but enough sand to make digging easier.”

Lichtenberg’s lab is now expanding the research to study how different grazing management strategies could impact both vegetation and pollinators.

“This previous study looked at one grazing management style,” Lichtenberg said. “Next, we want to explore how varying approaches could impact bee populations.”

Collins, now with The Phoenix Conservancy in Washington State, continues restoration work in endangered prairie ecosystems — work she said was inspired by this research.

“My work on the ground-nesting bee study is what got me interested in how different disturbances impact ecological communities,” Collins said.

To help native bees, Collins recommends planting native flowers and, when possible, leaving some bare patches of healthy soil for nesting. Even without a garden, she said there are ways to get involved.

“People can volunteer with pollinator organizations, collect data or take photos of bees. iNaturalist is a great place to start because you can upload what pollinators you see to help track what’s in your area,” Collins said. “One of our biggest challenges is simply not having enough data — and anyone can help with that.”